Could gold be the basis for a new global currency?

Cover story from this week's Moneyweek

This is the cover story which I wrote for this week’s Moneyweek. Regular readers will be well aware of the themes, which I have covered here quite a bit recently.

Gold and gold miners are back in a downtrend. Occasionally, there are glimmers of hope, only for the sellers to come piling back in. The slide began shortly after the commodities spike in the spring following Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, and it has been relentless. Your author shakes his head. Isn’t gold supposed to go up during times of war? Isn’t it the go-to asset in times of inflation? Apparently not.

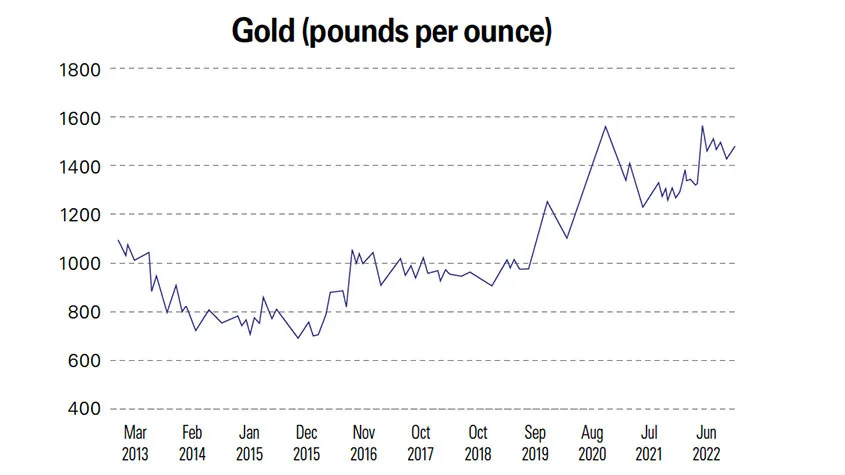

However, if one views gold as simply another currency, then its performance has not been as bad as the headline numbers suggest. It has not done as well as the dollar, but it has outstripped the pound and the euro. Even though gold is quoted in US dollars, the dollar price of gold is irrelevant to us British investors. If you pay pounds to buy gold, and you will eventually sell for pounds, all that matters is the sterling price of gold.

The chart below shows gold in pounds over the past ten years. Gold cost £700-£800 an ounce (oz) in 2014 and 2015, and is now just shy of £1,475/oz. It is not far off its highs around £1,575/oz and remains in a clear long-term uptrend. In other words, gold has done its job and hedged investors against the mess that has been sterling these last five years.

The ideal backdrop for gold

But, really, you want to see gold rising against all currencies. Panicking capital has been fleeing to the US dollar, which has been occupying the safe space that might normally belong to gold.

The US is tightening monetary policy faster than the UK, Japan or Europe and the prospect of higher yields on US assets has made the dollar more attractive. The US is ahead in the rate-rising cycle and until Japan, the UK and Europe start tightening as aggressively, the dollar is going to remain strong.

The ideal macroeconomic environment for gold is for equities to be weak and for government bond yields to be lower than expected inflation. At present we have the former, but not the latter. Longer-term inflation expectations are still below 3%. If they were at 8% or 10%, but rates were 5%, then capital would seek out the alternative that is gold. That is when so-called real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates are negative.

You want to be at a point where central banks are reluctant to raise rates and yet inflation won’t go away – in the US, at least, we do not have that. Yet. How permanent is this inflationary episode? How much will central banks raise rates? These are all questions we must answer if we are to make the decision to buy gold. Inflation might come down a little as weaker oil and metals prices filter through, but I think we’ll remember pre-Covid inflation numbers as halcyon.

Another issue to ponder is whether gold is an analogue asset struggling to adapt to a digital age. Gold is perhaps the oldest substance on earth. It was present in the dust which formed the solar system four-and-a-half billion years ago and its origins are thought to lie in supernovae and the collision of neutron stars. It came to earth via the asteroids that then bombarded the planet.

While highly malleable, it is also the most permanent substance, thought to be indestructible. All the gold that came to earth all those billions of years ago is still intact. You can batter it into a film just one atom thick but you cannot destroy gold. As a result, all the gold that has ever been mined, save that which has been dissolved in aqua regia, is thought to still exist, even if lost.

That’s why gold has been such good money. It lasts. Value today, however, is almost entirely digital. Money itself is digital: just 2%-3% of Western money exists as cash. The bond market is mostly digital. Software, intellectual property (IP), cryptocurrency – digital is where the value is. It’s also where most of Western growth has been these past 30 years.

Russia and China could develop a new global currency

Rapid recent geopolitical developments, however, suggest that gold is far from irrelevant. A new gold-backed currency could emerge. With Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, I was quite amazed by the speed at which the US weaponised the dollar and the banking system. Some $300bn in Russian central bank assets were confiscated (about one fifth of Russian annual GDP) and Russia was frozen out of SWIFT, the international payments system. Putin retaliated by demanding roubles for Russian gas. The currency wars well and truly began.

If Russia is not to be isolated internationally, it needs an international currency it can trade with. Just last month Putin said, “The issue of creating an international reserve currency based on a basket of currencies of our countries is being worked out.”

Sergey Glazyev, a former Kremlin adviser, now minister in charge of integration and macroeconomics of the Eurasia Economic Union (EAEU), is, it seems, supervising a new money system for the EAEU and China. “The world’s new monetary system, underpinned by a digital currency, will be backed by a basket of new foreign currencies and natural resources”.

“All interested countries will be able to join. The weight of each currency in the basket could be proportional to the GDP of each country, its share in international trade, as well as population and territory size. In addition, the basket could contain an index of prices of main exchange-traded commodities: gold and other precious metals, key industrial metals, hydrocarbons, grains, sugar, as well as water and other natural resources.”

Western nations may have shunned the “Russian Davos” in June – the St Petersburg International Economic Forum – but key representatives from China, India, Iran, Turkey and many Arab nations were there. The recurring theme was trade between non-Western powers in a US dollar-controlled world of sanctions and a new, non-Western international currency.

Meanwhile we have the The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), which had its latest summit last week in Samarkand, Uzbekistan. In terms of geographical scope and population, it is the world’s largest regional organisation, covering 40% of the world population and over 30% of global GDP. Its members are China, Russia, India, Pakistan, Iran (which just joined), Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. And Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdogan says he is considering membership. These are not exactly pro-Western nations.

Both Putin and Xi Jinping of China called for a reshaping of the international system. Various infrastructure projects being developed, notably a trans-Afghan railway to link Uzbekistan to Pakistan, a China-Central Asia natural gas pipeline and a China-Kazakhstan-Uzbekistan railway. China, which, as we know, is beholden to both Europe and the US for its exports, clearly wants to open up new markets.

Are these nations seriously going to want to trade in dollars? You can bet your bottom dollar that many of China and Eurasia’s brightest minds are plotting an alternative system. But it’s a lot easier said than done.

The problem of trust

To back a currency with commodities would raise all sorts of problems relating to storing raw materials. And if you use futures, you need to trust your trading partner. It is the same with systems based around government debt, GDP and fiat currencies, too.

The record of the regimes involved is hardly unblemished. The body language between the various leaders, especially China and Russia, does not suggest total trust. How then to make a money system that is practical and that everyone can trust?

The answer is an obvious shiny yellow material, analogue asset in a digital world or not. It is often bandied about that among China’s many ambitions is for the yuan to be the global reserve currency. But every international reserve currency in history started out backed by gold. Whether it was the pound, the dollar, the florin or the currencies of the ancient world, they were all at least as good as gold, if not gold itself.

They may have ended up debased into oblivion, but they started off backed by gold and sometimes some silver, too. It was only because the money was sound that it won global trust in the first place. Even John Maynard Keynes (who in 1924 declared the gold standard a barbarous relic) in 1942 proposed a supranational currency backed by gold: the bancor. Would such a system be practical today? I think so.

Who owns the gold makes the rules

We know that many countries in the SCO have plenty of gold and have been increasing their holdings. In the 14 years between 2006 and 2020, Russia’s central bank more than quintupled the country’s gold holdings, from around 400 tonnes to today’s 2,300 tonnes or so. It’s now world’s fifth-largest gold owner.

Then there is China. It has been quietly de-dollarising. Since 2021 China has lowered its holdings of both dollars and US Treasuries by 10%. Its holdings in US Treasuries have dropped by over $100bn since 2021, and it now has less than $1trn in US debt for the first time since 2010.

Its US dollar foreign-exchange reserves have come down from $3.25trn to $3trn over the same period. Having seen what happened to Russia, China will not want to be too vulnerable to a banking system that is run by the West.

Then there are China’s gold holdings. I consider this the most important story in world finance, yet it is largely ignored. China has far more gold than it says. China’s stated reserves are 1,948 tonnes of gold (barely 3% of its foreign exchange reserves). America’s are 8,100 tonnes (over 65% of national reserves).

Now we consider Chinese mining and its imports. China is the world’s largest producer of gold. This past decade it has produced about 15% of all the gold mined in the world. Since 2000, China has mined roughly 6,830 tonnes. China keeps the gold it mines. Over half of Chinese gold production is state-owned, and the export of domestic mine production is not allowed.

Given 6,830 tonnes of production, its official 1,948 figure already looks dubious. Chinese mining companies have also been buying assets across Africa, South America and Asia, and international production now exceeds domestic production (by approximately 15 tonnes in 2020).

China is also the world’s top importer of gold. Imports via Hong Kong alone, never mind Switzerland or Dubai (for which we don’t have numbers), have amounted to more than 6,700 tonnes since 2000.

Most of the gold that enters China goes through the Shanghai Gold Exchange (SGE), so the SGE is a proxy for demand. We know that since 2008, 22,000 tonnes of gold has been purchased by and delivered to physical gold buyers in China.

There is also gold that enters China that isn’t accounted for by SGE withdrawals. The central bank oversees the SGE, but its purchases do not go through it. It likes to buy 12.5 kilogram (kg) bars, which do not trade on the SGE, and it often uses dollars on exchanges in London, Dubai and Switzerland, while the SGE sells its gold in yuan. So there is plenty of tonnage we cannot account for.

Add to this gold held in China, whether as bullion or jewellery, prior to 2000 – the World Gold Council estimates 2,500 tonnes in privately-held jewellery – plus domestic mining and official reserves, you get a figure of around 4,000 tonnes. Cobble it all together – cumulative production, imports and existing stock – and you arrive at a figure around 32,700 tonnes. That’s just what we know of.

I have spoken to numerous analysts and they all arrive at similar estimates. Alasdair Macleod of Goldmoney thinks it is higher still. How much of this gold is state-owned?

Remember there are numerous other state bodies besides the central bank that own gold: the army, the State Administration of Foreign Exchange and China Investment Corporation, the sovereign wealth fund. Precious metals analyst Bron Suchecki, formerly of the Perth Mint, says 55%.

Even at 50%, the implication is that China owns more than 16,350 tonnes – double the US figure. I can’t see how its national holdings are anything like the 1,948 tonnes they say they are. To declare markedly larger holdings would cause an unwanted surge in both the yuan and the gold price.

The state’s US dollar reserves would be devalued. It would be a direct challenge to US supremacy. China is probably not yet ready for that. For now it follows Deng Xiaoping’s doctrine: “We must not shine too brightly.”

But if that Russia-China axis wants to weaponise money, as the US has done, all China has to do is declare its gold holdings, and perhaps even partially back the new currency it plans to launch, a central bank-backed digital yuan, with them.

Unbacked Western fiat money risks losing a great deal of its purchasing power in such an event. It could create chaos in the West. But that is the card China now has with its 20 years of relentless accumulation.

In short, any new money whose aim is to get SCO trading with each other outside of a US-controlled banking system is going to need to involve gold for it to work. It wouldn’t surprise me to see them attempt the Glazyev system described above and for it not to work because of the trust problem, and because most of those nations are going to want to retain the right to print. They could then try a second time, giving gold a more prominent role, and this time it might work better.

Far from being an irrelevant, antiquated asset, then, gold could well prove the key to a new currency spearheaded by China and Russia in the medium term. In the meantime, as MoneyWeek often points out, inflation could well become entrenched (see page 5), so the scenario of bond yields lagging inflation expectations may be with us before too long. Hedging your portfolio with gold remains a good idea.

There are several ways to gain exposure to the yellow metal. You can buy gold bullion via the the Pure Gold Company. I also like Goldcore in Dublin. Tell them I sent you. you can put an exchange-traded fund (ETF), which tracks the spot price, in your portfolio. My full guide to buying gold is here:

If China plays its gold trump card, miners, currently performing very badly, are going to see a dramatic upward revaluation of their properties. Here’s hoping.

This article first appeared at Moneyweek.

Finally if you are in London this week on September 29, my lecture with funny bits, How Heavy?, about the history of weights and measures is coming to the Museum of Comedy. It’s a 7-8pm show so you can come along and go out for dinner after. You can buy tickets here. This is a very interesting subject - effectively how you perceive the world. Hope to see you there.

Last I heard the Russian central bank was selling gold. How does that fit in?