Imagine you are a prospector, out there in the wild somewhere, exploring for natural resources - for gold or oil or diamonds.

Most of the easy-to-find stuff has long since been discovered and mined, so the chances are you are somewhere remote and inhospitable. It might be really cold, really hot, really high or really far. Never mind the natural dangers, there might be other reasons to fear for your safety: political risk, little or no rule of law, war even.

But let’s just say you find something. You hit the motherlode. You’re made for life. All that risk was worth it.

Or was it?

You might be able to sell your discovery to someone else. But whoever buys it has got a big problem on their hands. If we are talking metal, it is going to take them 15 years before they receive any return on their investment. That’s the average time it now takes to bring a mine from discovery to production. 16 years! In 16 years I’ll be almost 70.

So much can go wrong in 16 years. The price of the underlying commodity can fall. Credit markets can dry up. The political situation can change. An anti-mining narrative can take hold. And all the while that would-be mine is draining enormous amounts of capital. It is not just the construction of the mine that takes so long and costs so much, but the marketing, the financing, the miles and miles of exploratory drilling that need to be done, never mind all the other developmental work, to define the resource.

Mining is a very difficult industry.

It’s great in a bull market. But bull markets are few and far between. The rest of the time it is hard.

It’s why, so often, a better way to play a metal is, rather than own a company that mines for it, to own the metal itself. Here, for example, is gold (in red) against the gold mining companies (in black) since the turn of the century. Gold has done a lot better than the companies that produce it.

This is more a curse of precious metals than it is base and industrial metals. Copper miners for example have actually outperformed copper over the last decade. Silver, which is both industrial and precious metal, has only marginally beaten the miners, although, to be frank, both - silver and silver miners - have been crap.

In the 1930s and the 1970s gold miners outperformed gold. But since 2000, with the plethora of ways there now are to own gold or get exposure to the gold price (ETFs, online bullion dealers, bullion by post, futures, options, spreadbets and CFDs), and with the plethora of problems that have hit mining, owning gold has been a better bet than owning the miners. This isn’t the case during runaway mining bull markets, such as in the first half of 2016, but it has been the general rule. (There are also many individual cases of well run mining companies bucking the overall trend).

Uranium mining is even worse

But if it takes 16 years to bring the average mine from discovery to production, a uranium mine takes even longer. There are all sorts of reasons for this and most of them are regulatory.

(If you want to read my special report on uranium, by the way, it is here).

It’s blindingly obvious to everyone except policy makers that nuclear is the best solution to both the energy crisis in which the world finds itself, and the environmental issues around the burning of fossil fuels. The world is going to need more uranium.

But it is also blindingly obvious that many of the world’s leading uranium mining companies are not going to see any production for another ten years at least, in some cases another 20. The desirability of their deposits may increase, drilling may prove them to be larger than thought, but they are still going to be massive black holes of capital until that faraway time in the future when they start profitably producing. Many of the top 30 uranium miners by market cap, in my view, will never see any production at all.

What, then, is the point of investing in them? It’s greater fool theory. You buy, even if the underlying business is not sound, because you think you are going to be off-load at a higher price later on. Even if I am bullish about uranium - I think it should be a core part of any portfolio - I am ambivalent about uranium miners.

The Sprott Uranium Mining ETF (LSE:URNM) contains 37 uranium companies, including Cameco Corp (17%), NAC Kazatomprom JSC (13.5%), Sprott Physical Uranium Trust (13%), Denison Mines Corp. (5%), NexGen Energy Ltd (5.18%), Energy Fuels Inc (5%), and Paladin (5%). Of those companies, to my knowledge, barely more than two - Cameco (TSX: CCO) and Kazatomprom (FRA: 0ZQ) - are successfully producing.

So in buying that uranium mining ETF, then, you are in effect buying a basket of companies that are net drains on capital. What is the point of buying 30 net drains on capital? I listened to a presentation by one of the companies on that list last year and the CEO argued that the reason to own the company was that it is in the ETF and so it will rise with the sector. There’s no hope of it actually producing. It’s a classic lifestyle company.

There’s a similar story with the Global X Uranium ETF (NYSE:URA), although that has some companies, such as Mitsubishi, that operate in and around the space - nuclear tech you could say. The same goes for the VanEck Uranium and Nuclear Technologies UCITS ETF (LSE:NUCL).

There is a strong case for investing in nuclear tech, by the way. I have been arguing for Rolls-Royce (LSE: RR) almost since this Substack began, because of the contracts to build small modular reactors which it is likely to win. The stock has done very well and gone from below 90p north of 200p.

But nuclear tech is not the same as uranium per se. At present the world is setting up for the mother of all uranium supply squeezes. Here’s why.

The coming supply squeeze in uranium

Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan account for roughly 53% of global uranium production. Historically, they would ship to the west through Russia, which they now can’t. To the east, China has said that it will not export uranium or allow it to be shipped through, as it needs the uranium itself. (China has 55 operating nuclear reactors, another 22 under construction and another 70 being planned - that in itself is reason to be bullish, though it’s hardly a new story). To the south lie Iran and Afghanistan - no can do. So the only remaining option is to ship across the Black Sea, where there is a war on. This would also require the agreement of Azerbaijan and Georgia, which is more problematic than it sounds. At present the Kazakhs do not have a route to the sea.

For now, the Kazakhs have met contractual agreements through existing warehouse stocks and swaps, but, as fund manager, Harris Kupperman, aka Kuppy, points out in his latest missive, that “isn’t sustainable and it increasingly seems like they will announce a Force Majeure”.

Russia and China account for another 8% of global production, and Niger, where there has just been a coup, another 5%. In total, as Kuppy says, “roughly 66% of production is now offline to the West”.

Kuppy also projects 245 million pounds of demand next year against 170 million pounds of supply.

In short, the likely outcome is much higher prices.

How high do uranium prices go?

Here is uranium over the past five years. You can see it is in a clear uptrend.

Here’s uranium going back 25 years. You can see that, within the bigger picture, the uptrend of the last five years is actually quite moderate.

Note the 2003 to 2006 period when mania gradually took hold and it went to $150/lb. Uranium

Based on previous price patterns, I don’t think a re-test of the old high around $150/lb is at all an unrealistic possibility. If the kind of shortage that Kuppy is describing manifests itself, and the uranium narrative takes hold in the broader psyche, then things really could get nuts.

How to play a uranium price squeeze

While I like nuclear tech, it is not necessarily the best way to play a uranium price squeeze.

What then, if not mining, is the best way to play this inevitable uranium theme?

The obvious answer, and the most low-risk way of playing this, is, simply, to own uranium itself. There are two ways of doing that.

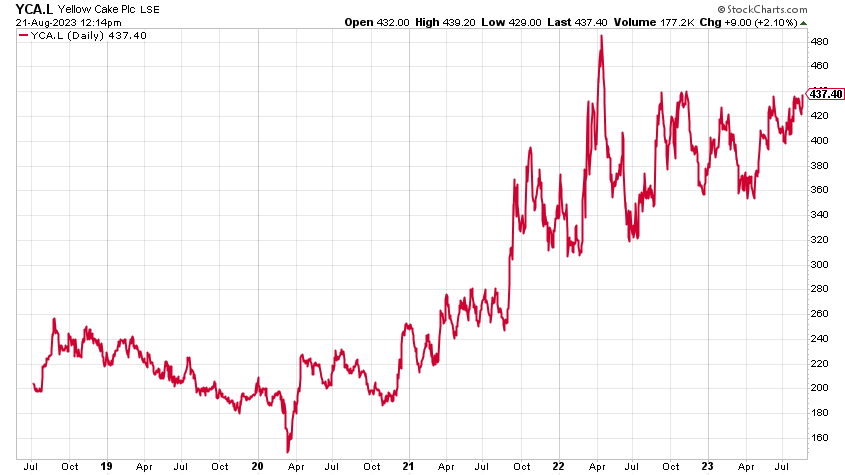

For many years I have been arguing for London-listed Yellowcake (LSE: YCA). It is, basically, a uranium holding company. You buy the shares and, in effect, own physical uranium. It has done very well. Market cap is £890million. It trades at a slight discount to its NAV.

North American readers will prefer the Sprott Physical Uranium Trust (U.U.TO/U.UN.TO), which is the world's largest physical uranium fund. Market cap is around $4.6bn.

It doesn’t really matter which you choose. The play is the same. Probably best to go with whichever currency is local to you.

Uranium miners may well rise by even more. But the risk with them is much higher, for all the capital-draining reasons I have described above.

If you want to read my more detailed special report on uranium from earlier this year, it is here:

Special Report: How to Invest in Uranium

I’m forever telling anyone who’ll listen that for all the money that has been thrown at green energy tech in the last 20 years, 84% of global energy still derives from the burning of fossil fuels. Just 4% is nuclear. Energy use breaks down into three main categories: transportation, heating and electricity. One third of demand for energy is accounted for by electricity; 63% of electricity in turn stems from burning fossil fuels. Wind power makes up just 5%, solar less than 3% and nuclear power 10%.

Disclaimer: I am not regulated by the FCA or any other body as a financial advisor, so anything you read above does not constitute regulated financial advice. It is an expression of opinion only. Natural resource stocks are famously risky, , so please do your own due diligence and if in any doubt consult with a financial advisor. Markets go down as well as up. I do not know your personal financial circumstances, only you do, but never speculate with money you can’t afford to lose.

Great article Dominic - did not realise that Uzbekistan & Kazakhstan were so involved in uranium mining - I will ask my boots on the ground what they are saying and report back if anything else is worth mentioning. Looking forward to the low-effort portfolio suggestions.