You Must Invest in America

Sensible Investments with Dr John

Dr John and I are working on the idea of a cockroach portfolio: that is a portfolio that will survive all weather, one that you can put together and then, broadly speaking, forget about. You don’t need to keep looking at it every day, worrying about this or that position. I wanted to call it the Do Nothing portfolio, or similar. It would contain some gold, some bitcoin, some energy, some real estate, some Asia exposure - and so on. Watch this space for more on that.

In the meantime, here is Dr John making the case that any such portfolio should have plenty of exposure to the USA.

It’s quite appealing, to me at least, to think of a resilient portfolio that one can simply invest in and then forget. A portfolio that would somehow magically navigate through all the market turmoil, protect you in crashes and provide market-beating returns in bull runs. This indeed is a driver for part of my investing approach.

Ruffer Investment Company (LSE:RICA) does a good job at this, generally. It’s one of my largest holdings. But I don’t think we can just say invest in Ruffer; it’s too cautious, I think, for the very long term (it’s only been going 20 years).

I’ve been talking to Dominic for a while about a 100-year portfolio: I think 100 years is a stretch, but I’m prepared to have a stab at 50 years. We’ll present it next time, but for now here are a couple of spoilers. The first of these is that: for the long-term, you simply have to bite the bullet and invest.

This is perhaps best explained through a cautionary tale about being out of the markets, any markets where you might want exposure.

When it comes to buying a house, my sister has never succeeded - should you ever read this, Jane, it is not a criticism. In the early days (the 80s for her) she didn’t want to make a commitment. This is reasonable enough if you love travelling, as she does. Then in the late 80s, she felt prices were too high and perhaps rightly resisted.

Of course, in the early 90s, there was no need to buy a house because prices were going nowhere. Many suffered negative equity, and that put new buyers off.

Then prices rose 20% in a year. At that point it seemed better to wait a bit for a correction, but they rose even more, doubling from the mid-80s low.

That correction never came.

The 2009 financial crisis eventually did cause prices to fall, but, to sceptics like my sister, this did not represent a buying opportunity. It meant, surely, that the world was coming to an end and capitalism was doomed.

After prices stabilised, zero interest rates kept house prices artificially high and raised fears of a crash when the zero rates ended. Now we are returning to normal interest rates, it really cannot be the time to buy because the crash hasn’t happened yet. Surely?

House prices have gone up a lot over the last 40 years, as we all know. With the UK tax system any capital gains would be tax-free, and of course you’d have lived rent-free.

The reason I’m not criticising you, Jane, is that I am also guilty of prevarication. I’ve never bought the S&P 500. There has always been a reason to not invest. I won’t bore you with what they are. They have proved as wrong as my sister’s and I’m supposed to be a good investor. Suffice to say, in this regard at least, I’ve been wrong for the past 40 years.

Warren Buffet, widely recognised as one of the best investors of all time, rightly doesn’t agree with me. He thinks that for most people, the best way of investing in stocks is simply to be exposed to the S&P500 index of America’s largest 500 public companies. He basically is saying three things: you cannot time the market, it’s very hard to find fund managers that will outperform the market, and that you should never bet against America.

I think it is time to accept that he is somewhat right, to say the least. The FT reported recently that the USA is now one-third bigger than Europe (including the UK) in terms of GDP; 15 years ago, they were roughly the same size.

So, what has this got to do with a 50-year portfolio?

A 50-year portfolio has to include the USA, predominantly the S&P500.

Not in the future after some anticipated crash, but now. If you meet anyone that thinks not, I would advise you to turn in the opposite direction and run. These are 500 enormously successful companies run by greedy, capitalist, visionary, entrepreneurial, hard-working, inventive managers. They have shareholders breathing down their necks to make more and more money, and to make that share price go up.

Hey, that’s not always the best way to make money, but I’m convinced it’s one of them.

My dilemma therefore is the same as my sister’s: How long do we wait before we invest?

We have to accept that sometimes even if assets are somewhat overvalued, you need to be invested in them. You can’t run and permanently hide in cash, gold, bitcoin, junk-debt, bonds, property, mining, oil and gas, smaller companies, biotech, emerging markets, technology, infrastructure funds, private equity (I’m partly talking to myself here). All of these will outperform and all will underperform.

It sounds obvious, but if you want a 50-year portfolio, or anything like it, you have to invest in things that have a good chance of lasting 50 years.

For all its failings, America is one of those things. It has one of the best demographics in the West. It’s got the right kind of immigration with the brightest minds wanting to make their fortune there. It is one of the few countries left where freedoms are still protected, where there is some attempt to restrain the size of government, and making money legally is truly admired. Most importantly, America has both energy security and the world’s reserve currency.

Europe has none of these. Energy has every potential to become a truly momentous problem in Europe in the coming years.

How much to invest?

I think that we should have 35% of our investable wealth in the USA. I would divide this between the S&P500, S&P600 (US smaller companies) and private equity. I think that 20%, 7.5% and 7.5% is a good split.

Now I hear you (and myself) saying: But the S&P 500 is overvalued – isn’t it best to wait a bit? Well, in the crash, if it comes, firstly are you going to be able to invest or will you prevaricate? And secondly, when will you know we’ve hit bottom?

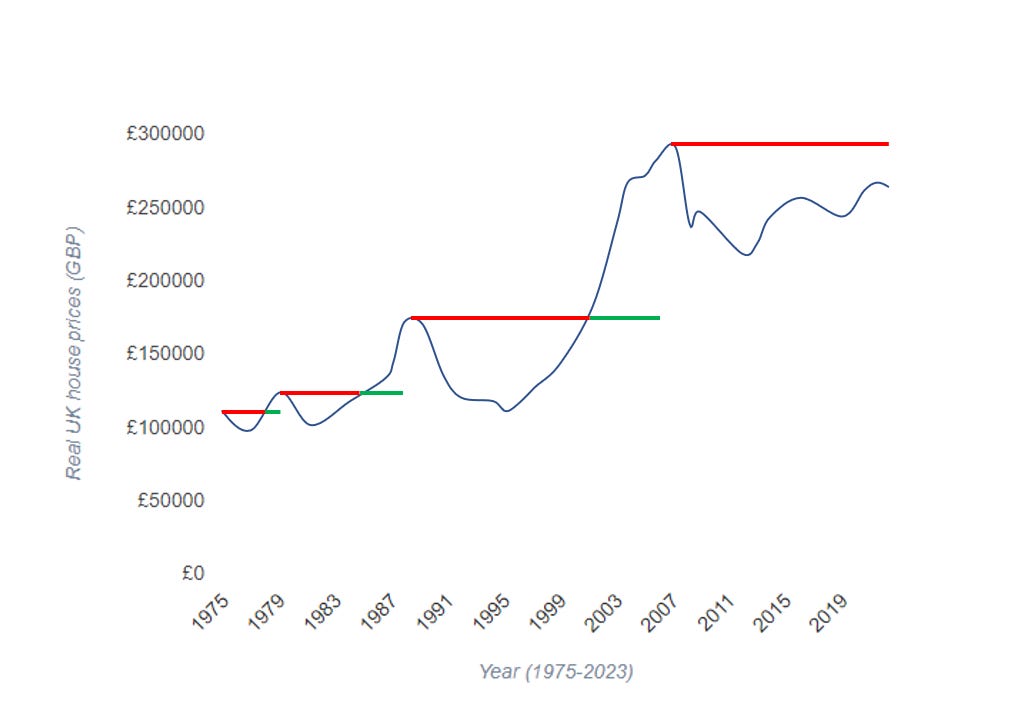

And the second spoiler? Let’s look at this chart of real UK house prices. We have a situation where, in real terms, an asset went from around £100,000 to £250,000 over almost 50 years. (In nominal terms, housing went up by more: it’s one of the few ways by which ordinary people have been able to get exposure to money supply growth).

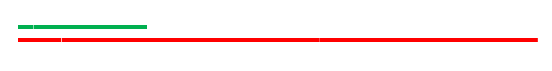

And in that period, look at the times when prices just didn’t strike out above a previous inflation-adjusted high (red) and when they did (green):

To be clear, look at the length of these two lines: