Before we begin today’s piece, a quick reminder for those who might find themselves in the Scottish neck of the woods this August, I am doing a show at the Edinburgh Fringe all about gold.

It’s from August 4th to 20th at 2pm. Please come if you are in town- you can get tickets here.

Plus an added bit of history: it takes place in the room in which Adam Smith wrote Wealth of Nations. Hopefully, I will see you there.

And, if you would like me to speak at your event or to advertise on these pages, please drop me a line.

Copper, they say, is the metal with a PHD in economics. Gold, eternal and indestructible, will protect your wealth. It might even give you safe passage into the afterlife, at least that’s what the Ancient Egyptians thought.

Zinc, on the other hand, stinks.

That is the cruel verdict the poets of the investment world have bestowed on zinc, and there is plenty of truth to the maxim. In the spring of 2022, zinc was flirting with $4,500 a tonne. Here we are 14 months on and the price is down $2,000 - $2,400/t at time of writing. Not only does zinc stink, it sinks.

It’s a story common among metals, but zinc really has been bad. Amongst LME-traded metals only nickel has been worse.

China’s post-Covid bounceback was supposed to herald good times for metals investors. No such luck. Global demand for zinc fell by 4% last year, led by a decline of 6% in Chinese demand.

The International Lead and Zinc Study Group (ILZSG) forecast supply shortfalls of 150,000 tonnes last October. For the first four months of 2023, it has just reported that the global market for refined zinc was in surplus by 138,000 tonnes. That’s probably why the price of zinc keeps sinking.

Zinc stockpiles at the London Metals Exchange (LME) were low at the start of the year, equivalent to less than two days' worth of global consumption. While stockpiles are low, there is always a chance of supply shortages and then price spikes, but they have since quadrupled and spreads suggest further inventory is expected. It is hard to be bullish when there is no shortage of supply and no unusually large demand.

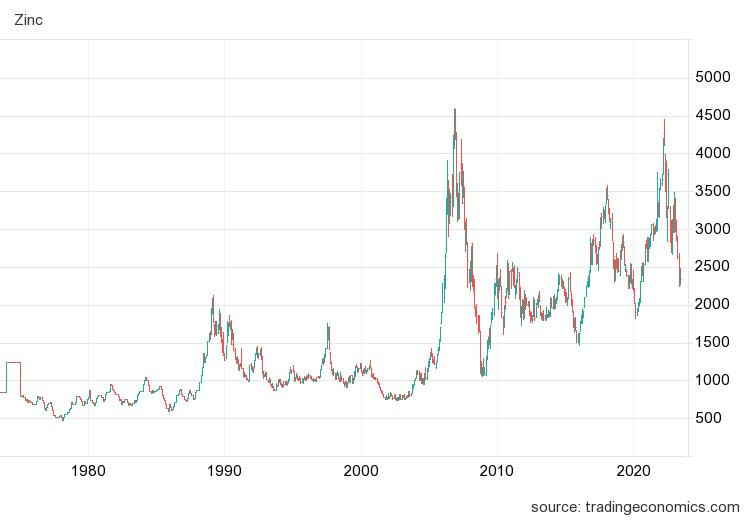

Here, for your information, is a chart showing 50 years of zinc prices.

That said there is a clear long-term trend since 2000 of higher lows.

Just over $4,500/t was the all-time high in 2008, during a decade in which all raw materials boomed.

You can see the barren commodities depression of the 1990s, by the end of which zinc had slid to $750/t; the incredible boom of the 2000s; more depression between 2011 and 2015.

2016 and 2017 were good years for zinc - by then there was a considerable shortage in supply. Exploration and development budgets had been slashed almost to zero, and there were genuine shortages of the metal.

Things turned down again in 2018, leading to an eventual low in 2020 at the height of the Covid panic below $2,000/t. It fell pretty much in tandem with emerging markets, as is often the way with commodities.

Much of zinc’s poor performance can be explained by its ties with steel. Zinc was caught in the crossfire of trade wars and, in particular, the tariffs on steel products.

Coming out of 2020, however, it had a bonanza run, eventually peaking in early 2022 with quite some spike, caused by Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. We were back near $4,500/t. Since then we have been in near free fall. It would appear the 2020 Covid-19 lows at 2,000/t are beckoning again.

Around $2,400/t, however, most mines do not make money. Many actually lose. A prolonged period around these levels will trigger output cuts. It’s already starting to happen. For example, Sweden's Boliden (BOL.ST), recently put its cash-flow-negative Tara mine in Ireland under maintenance. 650 workers laid off. Closing a mine is not only damaging to communities, it is expensive. Such decisions are not taken lightly. But stinking zinc has its first victim. Tara is Europe's largest zinc mine, the eighth-largest in the world.

Other mines will probably have to close too. There are thought to be 22 significant zinc mines outside China (including Tara) with all-in-sustaining costs higher than $2,400/t. This will lead to a shortage of supply and, eventually, price rises. Thus does the mining cycle of life - and death - continue to turn.

Why do we need zinc?

First isolated in India around the year 1300 (much earlier than in Europe), zinc now is the fourth most used metal in the world, after iron, copper and aluminium. Its main use is in the construction industry: the frames of buildings, bridges, roofs, staircases, beams and piping all contain zinc. A coating of zinc over iron or steel protects the metal beneath from rusting.

It is also used in alloys (brass and bronze), in compounds with a range of applications, particularly in batteries – from everyday AAs and AAAs to silver-zinc batteries in aerospace – and, increasingly, in fertiliser.

Around 60% of zinc usage is in the form of galvanised steel, which is widely used in the construction and automotive sectors. That is where demand has been weak.

There is also a narrative emerging around zinc battery storage. Zinc batteries offer a wider operating temperature range, longer life, and a lower cost per kilowatt hour than today’s leading batteries, including lithium.

The market for zinc is worth around $35bn a year. Numbers like that can be difficult to fathom, so to put $35bn in some kind of perspective, that’s around double the size of the lead and silver markets, but about a fifth of the size of the copper market.

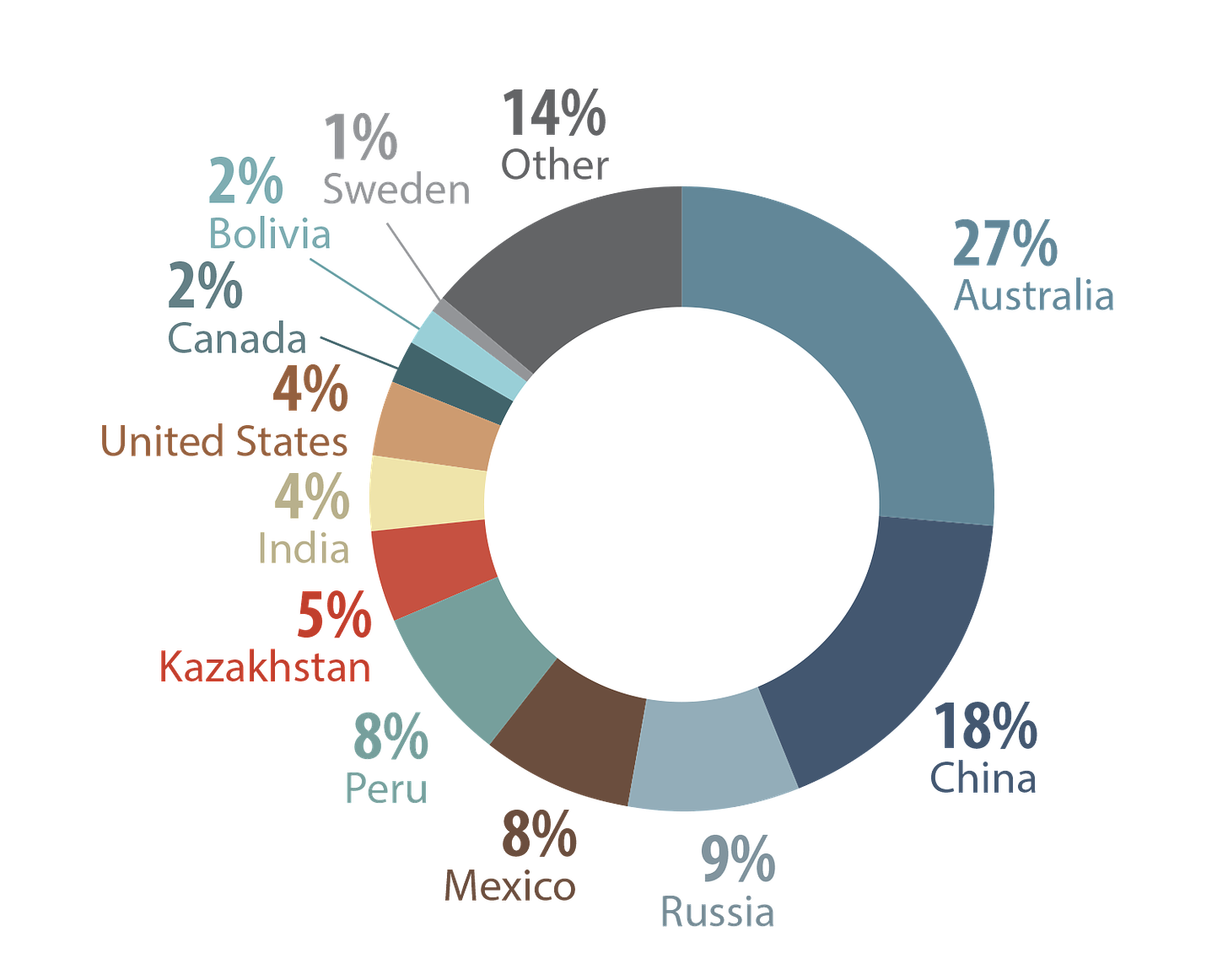

You guessed it. China is, by some margin, the world’s largest producer (33% of global production), the world’s largest refiner and the world’s largest consumer.

After China, the next biggest producers are Peru, Australia, India, the US and Mexico. Australia, however, has by some margin the largest reserves.

Just below 40% of zinc production derives from recycled or secondary zinc, especially from galvanised steel and batteries. (Galvanised steel tends to have a long shelf life). This is a tight market so it does not take a lot to knock it off balance. But both supply and demand have been pretty much in tandem this last decade, apart from a wobble in 2016-17.

Zinc’s time will come. But I’m not of the view that now is that time. That said, fortune favours the prepared. Bear markets are the time to get ready, to do your research, to work out the best ways to play the zinc game, so that you are ready to pull the trigger when we reach that inevitable point when demand increases and there is not the supply to meet it.

How to invest in zinc

There are a range of ways to play zinc. WisdomTree offers a London-listed ETF, (LSE:ZINC) , or you can spreadbet the price (which has its own considerable risks attached, and I’d avoid doing so unless you know what you are doing). The large miners are another option, but none are pure plays. Glencore (LSE:GLEN) is by some margin the world’s largest producer, followed by Hindustan Zinc (Mumbai:HINDZINC), Teck Resources (TSX:TECK) and Zijin Mining (SHAGHAI:601899). BHP Billiton (LSE: BLT), Vedanta (LSE: VED) and Sweden's Boliden (BOL.ST) are other options.

The largest mine in the world is in Algeria, the Ghazaouet Mine. Teck owns the next largest, the Red Dog Mine in Alaska. Vedanta own two of the “top ten”: the Rampura Agucha Mine in Rajasthan, India and the Gamsberg Project in Northern Cape, South Africa. Glencore also has two of the top ten - the Mount Isa Zinc Mine Queensland, Australia and the McArthur River Mine in Northern Territory, Australia.

As zinc often occurs with lead and silver, the largest silver producers often have significant zinc bi-product. And vice versa.

In the world of junior mining, there is no shortage of zinc plays. I have some legacy shares in dual-listed Solitario Zinc (NYSE: XPL; TSX: SLR), but the stock has gone to sleep. It has good high-grade projects in Peru and Alaska, both in partnership with majors, and as a result neither are being developed.

To be fair, management has kept the share structure tight. At 9% ownership, has plenty of skin in the game and there is a reasonable cash position. It is now working on developing a gold project that is promising, but you get the impression the project might have brought in to justify the existence of management, while its zinc properties are on hold.

I recently attended a gold show in Germany, the Deutsche Goldmesse, and saw one of the best presentations by a zinc company that I have seen by any company for some time. I’ll be covering that in my next Best In Class.

Interested in buying gold to protect yourself in these uncertain times? My current recommended bullion dealer in the UK is The Pure Gold Company, whether you are taking delivery or storing online. Premiums are low, quality of service is high. They deliver to the UK, US, Canada and Europe, or you can store your gold with them.

How to Invest in Zinc