Today’s missive comes to you from the Galapagos Islands out in the eastern Pacific, where two stories of noble energy initiatives reflect the broader realities of energy policy around the world.

We tell these stories with a specific question in mind: how much gas, so to speak, is left in the tank of this energy bull market?

The Galapagos population is only around 30,000, but, as a fully functioning society, the same dynamics observed in this small ecosystem occur elsewhere, even if less visibly, so it serves as a useful case study.

So we come to the first of our two stories.

Not so green transport in Galapagos

In order to limit traffic, protect the environment in this most ecologically delicate of places and protect the taxi industry, the local government made it extremely difficult to get a vehicle licence. All sorts of problematic bureaucratic hurdles had to be jumped, and most people ended up using bikes or public transport.

But then in 2016 the powers that be, with a brighter, greener future in mind, decided that anyone could get a licence to own a vehicle, no permit required - as long as it was an electric vehicle.

There was just one condition. The buyer had to have a family.

Given that most people on the islands have relations, that was a pretty easy condition to meet, even for the single folk.

There was a great deal of PR and fanfare about this new initiative: clean, green, sustainable - all that stuff - and a blind eye was turned to the increase in traffic, or of roadkill to the many tame birds on the streets of the island (this is a major problem).

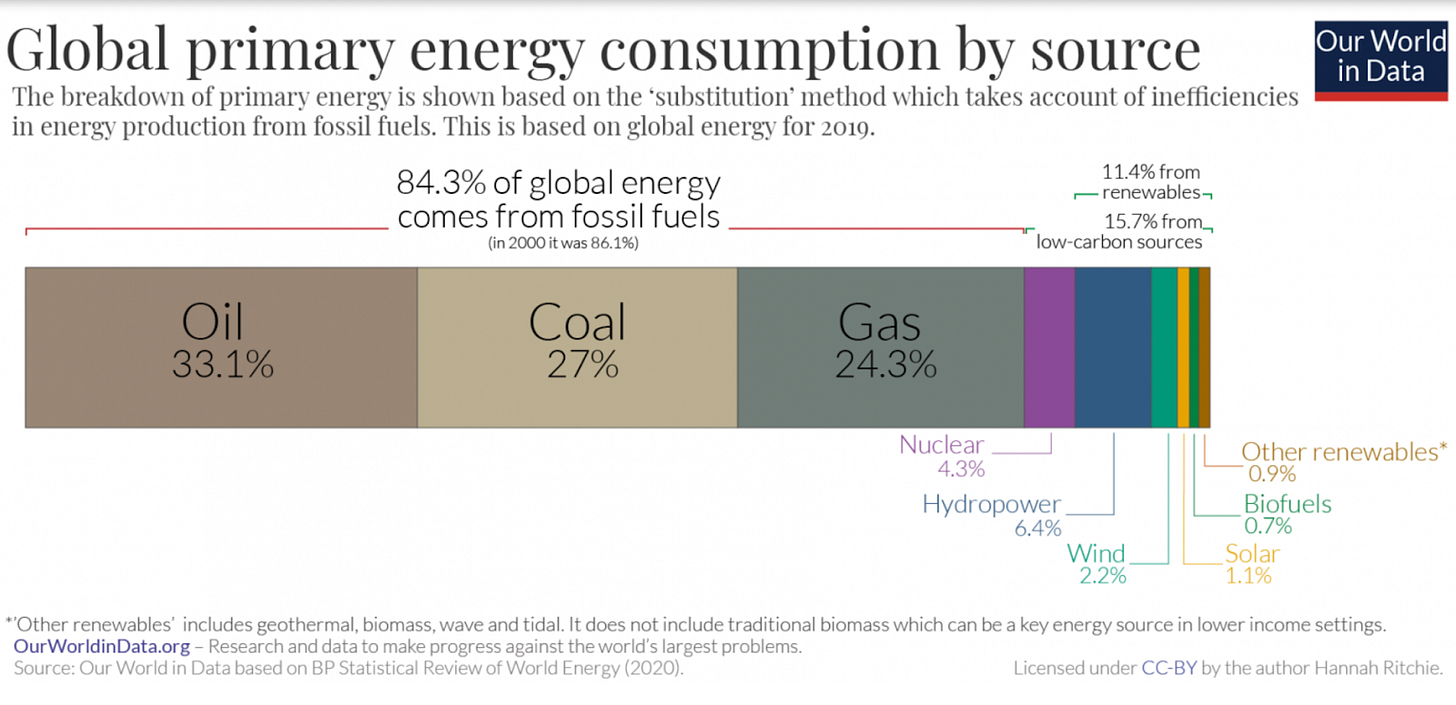

At this point it’s worth reminding ourselves that there are, around the world, three main areas of energy consumption - transportation, heating and electricity. While cleaner forms of energy, such as nuclear or wind, might be increasing as sources of electricity, 84% of global energy still derives from the burning of fossil fuels, as the graphic below from Our World In data shows.

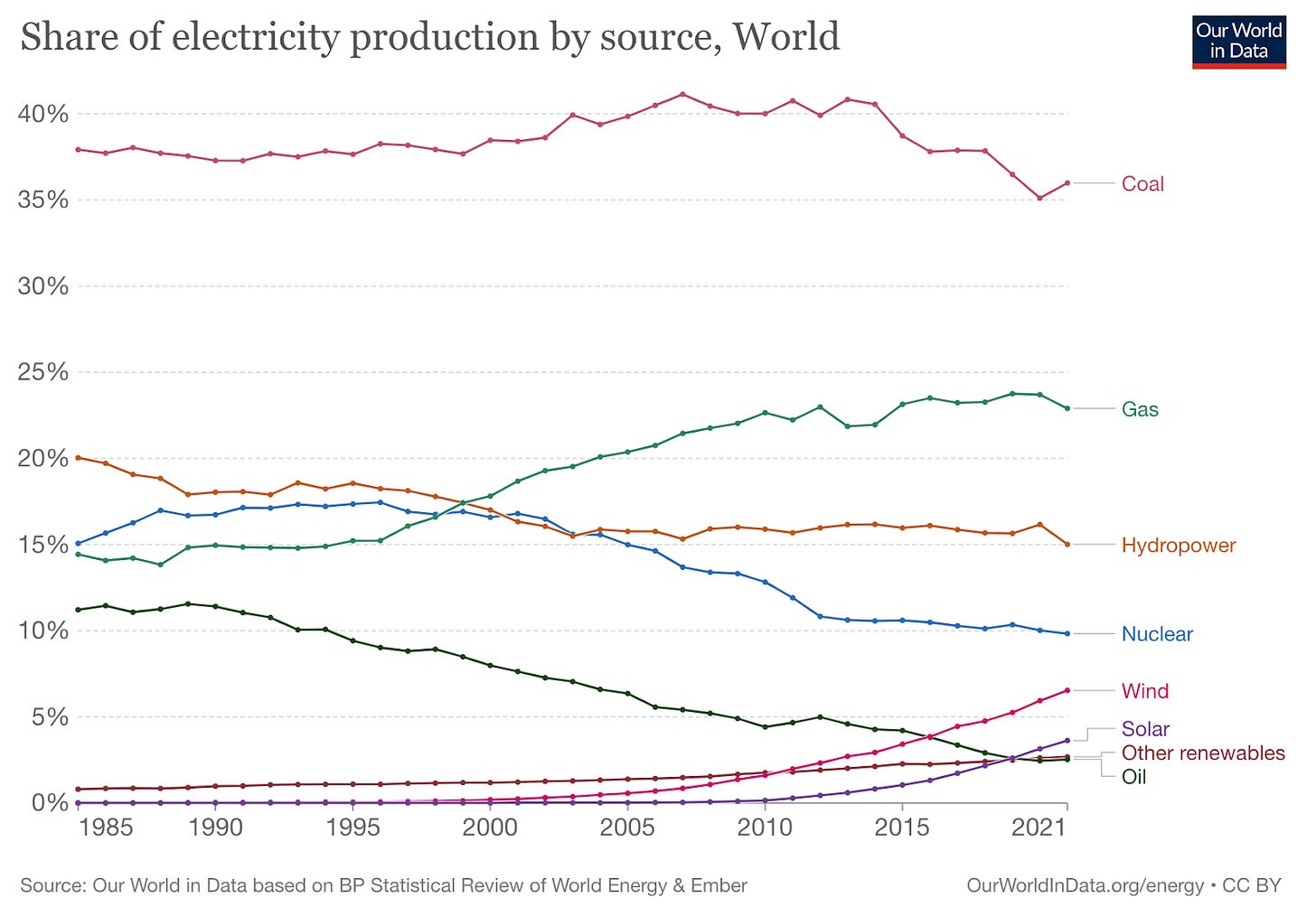

Even electricity, despite its green credentials, still relies on fossil fuels. The burning of the fossil fuel may be out of sight and, therefore, out of mind, but over 60% of global electricity still derives from it, as our second graphic shows.

Wind and solar between them account for barely 10%.

As we are all now discovering to our cost, despite many years of considerable investment, some might say over-investment, in green energy, there have, simultaneously, been many years of underinvestment in fossil fuel exploration and extraction, nuclear power (the use of which in electricity has, on a relative basis, been declining since the 1990s) and public grids. Hence the current energy shortages especially in Europe. The Galapagos Islands followed the international trends in this regard - which is one reason this story makes for such an interesting case study.

Here on the Galapagos Islands, the majority of electricity, despite what you may read, is produced by burning diesel. And at this point we deviate to story number two.

The Galapagos wind turbines.

There were, once upon a time, some wind turbines built by a consortium of overseas energy corporations, looking to advertise their green credentials to the world. Said corporations conducted a one-year study of wind on the island and concluded that next to the airport (where they would also conveniently be seen by everyone arriving at and leaving the islands) was the best place to erect the turbines.

The turbines were duly installed, the publicity was had - here is the world’s first airport that runs 100% on wind and solar, all that stuff - and the energy companies retired back to their nation states.

It turned out that year of the study had been an outlier for winds, and they hadn’t built the turbines in anything like the windiest spot.

Then the wind turbines stopped working, but nobody on the islands knew how to fix them. Nor was it clear whose responsibility they were.

Ever since, the turbines have sat there, stuck - even when the wind is blowing up a storm. Ask a local for the story, and you’ll get a wry shake of the head and a smile at the stupidity of it all. Lord knows how much fossil fuel was burnt mining the necessary materials, manufacturing the turbines, transporting them to the islands and erecting them, only for them not to work, but that is, despite the good intention, what has happened. There they remain, motionless, like statues from a fallen empire. But how now to get rid of them?

The episode is neither clean, green nor sustainable.

So back to story number one and the attempt to make the islands greener with electric vehicles (EVs).

With the easing of regulation in 2016, the locals who had previously wanted a vehicle but couldn’t get one (a lot) piled in and bought electric vehicles, much to the benefit of the EV manufacturers.

But as diesel is the major source of electricity on the islands, so more diesel than ever was now burnt. Again, neither clean nor green.

In fact so much diesel got burnt, and so much electricity was consumed, that the shortcomings of the grid and the lack of investment therein were exposed. Power outages soon followed. Multiple and regular.

The power outages got so bad that just three years after the EV fanfare, in 2019 a moratorium on electric vehicles was discreetly declared - no fanfare this time - and the islands went back to their old ways.

I can’t help thinking that the West is travelling a similar path. As consumers,, encouraged by the green credentials, adopt more electric vehicles, has there been a concomitant investment in power grids to meet the new demand? In many - dare I say most? - countries there hasn’t. What proportion of this rising new electricity demand will entail more burning of fossil fuel, coal especially? Will there be power outages as a result?

It’s stupid to expect us to consume less energy. As civilisations progress, they consume more energy. They also get better at consuming energy. A civilisation that consumes less energy is a civilisation in recession and decline.

We should not be advocating the consumption of less energy, but advocating the better and more efficient consumption of energy, and that means we have to invest in the exploration and production of fossil fuels.

How else is the developing world to pull out of poverty without the benefits of fossil fuels?

The International Energy Agency (IEA) forecast in 2020 in its World Energy Outlook that growth in global oil demand will only end in 10 years and that “global natural gas demand growth might stop around 2040”. Those two landmark years - 2030 and 2040 - are not when we stop using oil and gas, just when the demand for them stops increasing. (And they are probably optimistic forecasts).

That means that, to meet demand, not only do we have to maintain oil and gas production at current levels, we have to increase them - or prices will go a lot higher. That means greater investment in coal, oil and gas is required. And that means this bull market is far from over.

The whole narrative needs to change, as it is slowly starting to do.

There have been at least ten years of underinvestment in coal, oil and gas - partly because of the excesses of the last secular bull market and partly because of the powerful anti-fossil fuel story. That now needs to be corrected.

There is also now a strong case for a reversion to traditional auto manufacturers, as opposed to the likes of Tesla. But that’s a subject for another day.

Interested in buying gold? Check out the Pure Gold Company.

If you are in or around London on November 24, wearing my comedy hat, I’m doing a gig with the Gilets Jaunes - that’s my band - at Crazy Coqs in Piccadilly Circus underneath Brasserie Zedel. It’s a fantastic venue for this kind of thing. It’s going to be a great night. Please come on down.

This article first appeared at Moneyweek.